It’s common in revenue organizations to look at an unproductive rep and blame them for “not putting in the effort” or “not following the process”. While that can be the case, it’s worth pausing to ask yourself if you’ve orchestrated a system that enables reps to be effective.

In this post I’m going to take you through a framework for evaluating where opportunity lies for reps, identify some reasons that reps aren’t able to maximize that opportunity, and then provide some suggestions on how to improve. Sound good? Let’s go!

<record scratch> Actually hold on, let’s do a bit of setup first:

- We believe account-based ownership is best for modern B2B inside sales teams so I’ll use the term “account” throughout. If you use a mixed ownership model that includes leads, you can substitute “lead” for a lot of the below and it’s still applicable.

- This post is focused on the customer acquisition part of the revenue organization and generally works for both BDRs and AEs. Many of the same principles apply to managing existing customers but I’ll leave the details to a future post.

- When I talk about rep books, I'm referring to the set of accounts a rep is responsible for at any given time, regardless of whether they’re actively working them (more on that later).

Ok, we got that out of the way. Now let’s talk about quadrants!

Evaluating opportunity with the FT Quadrant

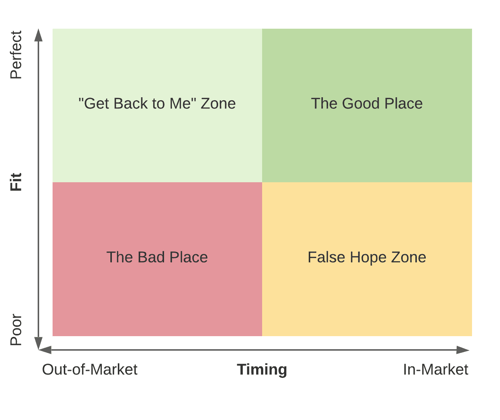

Here’s a simple way to think about the opportunity with any given account: fit and timing. When you put them together you get the FT Quadrant.

Let’s investigate how fit and timing operate within a sales cycle with an account:

- Fit - Does the account fit your Ideal Customer Profile? If they’re a fit, could they become a big customer? The higher up they are on the Y axis, the better they fit and the larger their value.

- Timing - Great accounts may not be ready to buy. Accounts are either ready and in market for a solution like yours (e.g. no current vendor, existing vendor contract is up, a new corporate direction means a desire for a new solution, budget is allocated) or they’re not (e.g. under contract with another vendor, budget is in flux, corporate priorities may mean they don’t value the solution, etc).

Any time you have two dimensions I’m pretty sure you’re legally obligated by the Rules of Business to name the quadrants. So, let’s do it:

- The Good Place - These accounts are a great fit and they’re ready to buy a solution. These are the opportunities you can win in the near future and, incidentally, where your reps should be spending most of their time.

- “Get Back to Me” (GBTM) Zone - These accounts are a great fit but the timing isn’t right. They may be under contract with their current vendor for the next year or there’s another major priority. When you engage, you’ll get the “sounds great but get back to me next quarter” brush off. (This is valuable information you can use in your processes. We’ll address this later.)

- False Hope Zone - These accounts are a poor fit but are currently in-market. I call this false hope because chances are good you can land some of these - after all they’re ready to buy something similar to what you offer. However, you’re likely to find that a) this process isn’t repeatable and b) they’re poor customers who will have service issues and be likely to churn. These will often come through your inbound demand gen channel. They’re especially pernicious because your team will have happy ears due to the timing and ignore signals about poor fit.

- The Bad Place - These accounts are neither a fit nor are they looking to buy. At best you’ll avoid these altogether, at worst your team spends time on a sales cycle with no chance of success. These frequently arise from poor prospecting efforts. If you have a geographic territory model, reps are in danger of spending a lot of time here unless they’re excellent at discovery and qualification.

The positions of accounts in these quadrants aren’t static; they can and do move. However, they don’t move along the two axes in the same way and your ability to influence the movement is constrained.

Timing changes predictably over, well, time. Accounts will oscillate back and forth between being in-market and out-of-market as they buy solutions, renew solutions, and go through budget cycles. While it’s not quite the same as predicting the orbit of planets (shoutout to Jupiter’s location in the year 3000), given enough information, you can probably predict most of these moves. Like the orbit of Jupiter, however, you’re pretty unlikely to be able to change an account’s timing if it’s truly set. You can buy out competitor contracts but this causes your CAC to skyrocket and you should only do it if you’ve got an absolutely ironclad LTV or if some friendly VCs have given you a pile of money to set on fire to find your way to Step 3.

Fit changes infrequently, if at all. There’s no guarantee that an account will ever move from being a poor fit to a good one or vice-versa. That requires a change to either the account’s business (e.g. they grow, they shrink, they radically change strategy) or your business (e.g. you offer a new product line that expands your sales-addressable market).

The takeaway here is that accounts in The Good Place are vastly more valuable than others but they’re only there for a limited time. It’s critical to engage with accounts as they enter The Good Place because they can quickly move into the GBTM Zone if you miss your window of opportunity. (This simple realization has led big chunks of the ABM martech industry to build around recognizing in-market buying signals.)

We’ll spend the rest of this post discussing what’s pushing your reps out of The Good Place and what you can do to keep them there.

Your reps aren’t staying in The Good Place

Given that you don’t have unlimited resources (if you do, please give us a call at Gradient Works; I think you would fit nicely in our ICP), you need to keep your reps focused on the accounts in The Good Place as much as possible. Unfortunately, reps often spend a lot of time outside The Good Place for several reasons.

First, let’s consider inbounds and their impact on human psychology. Inbounds are a semi-stochastic (stochastic is a fancy way of saying random that sounds smart; use it in your next meeting to sound like a big nerd) process that works like a variable reward schedule where we do something and occasionally get something good as a reward. BF Skinner (basically a real-life evil genius) performed a lot of reward and reinforcement experiments like this. He showed that the best way to get a behavior was to reward it inconsistently. These systems drive gambling addiction and the compulsive desire to check our email and social feeds. Inbounds are great for triggering this kind of behavior. You get a new lead seemingly at random and you might get a win - better work it right now! When our reps get an inbound, it takes every bit of discipline they have to convince themselves to disqualify this fantastic new opportunity before them. After all, this guy wants to buy now and yeah they’re not a perfect fit today but they’re going to hire several folks and they’ll be a big customer in a few months we just need to give them a 30% discount and get them in the door… This keeps reps coming back to the False Hope Zone.

Second, consider the other way reps get accounts: prospecting. It’s very hard to communicate your ICP perfectly to every rep (partly because companies rarely do a great job of defining their ICP in the first place). It’s even harder as a rep to hew exactly to the ICP as they prospect. When you give reps a territory to own and tell them to make the most of it, they’ll naturally fudge the ICP a bit to try to maximize value. This can lead them to spending too much time in the bottom two quadrants - after all, hope springs eternal.

Third, finding out it’s the wrong time takes time. Good reps stay focused on accounts within the ICP which means they’ll stay in the top two quadrants. That’s great! Unfortunately, it’s often impossible to tell if an account is in-market until you’ve invested time in doing outreach and discovery. This means that even very effective reps will still spend a lot of time in the GBTM Zone.

Finally, it’s easy to equate book size with book value. A rep with a book that’s too large will face the paradox of choice. If reps are responsible for too many accounts, it can become difficult for them to rationally choose where to focus their time. (A related and more colorful version is Buridan’s ass where a hungry donkey starves to death because he’s equidistant between two piles of delicious hay.) Absent a better way to choose, reps will likely focus on accounts that engage the most, putting them in danger of spending too much time in the False Hope zone. After all, lengthy, disciplined prospecting sessions are far less fun than talking to the guy who just might buy tomorrow.

Good Place guardrails

You should consider the FT Quadrant when designing your processes to provide guardrails that help your reps focus on The Good Place. The best way to do that is to ensure that rep books are weighted heavily towards accounts in The Good Place with minimal distractions from the other quadrants.

First, remove as much the timing burden as you can from the reps. This requires a system with some automation to a) notify reps to engage when an account is in-market and b) nurture accounts in the GBTM Zone with marketing messages to soften the ground for reps when the account moves back into The Good Place. There are entire ABM products built around this concept so I won’t go into all the mechanics here but I will address one under-utilized piece of information: the competitor renewal date. In a previous role in a highly competitive SaaS industry, we encouraged reps to learn when their accounts were renewing with a competitor and then allowed them to tag an account with a “Get Back to Me Date”. Sales Ops would then remove the account from their book, Marketing would nurture the account with marketing messages and then Sales Ops would automatically return the account to the previous rep at the right date. This was logistically a bit of pain but it encouraged reps to identify key timing without worrying that they might be giving up a future opportunity. By removing the account from their book entirely it kept the reps focused on active accounts, limiting distraction.

Second, specialize on qualification and reward it when it’s done properly. Most B2B inbound sales organizations already do some level of this with a BDR/SDR role. I highly recommend that you have a role that’s solely responsible for qualification of inbounds and prospects that sits in front of your AEs. Make sure you get the training and incentives right for these roles as they will be the most tempted to lower qualification standards and lead your downstream AEs to the lower half of the FT Quadrant. This means ruthlessly focusing on coaching and ICP criteria while ensuring that comp is based on sales acceptance of or even revenue from sourced opportunities.

Third, reduce the size of the active book. As I previously mentioned, too many options can be paralyzing and cause reps to focus in the wrong areas. I recommend keeping rep books relatively small. I tend to think about Dunbar’s number which (very roughly) indicates humans can maintain about 150 stable relationships at once. Think about your sales process and how many stakeholders are likely to be involved with each account and factor that into your book size. If you have a simple transactional sale to a single POC, perhaps a rep could have a book of 150 accounts. If you have a complex enterprise sale to multiple stakeholders maybe that number goes down quite a bit. The good news is that a complex multiple stakeholder sale should usually align with higher ASP so the potential value of the book should stay about the same.

One problem with geographic territories is that they can create large books in some geographies, exacerbating the focus problem for those reps. If your sales process relies heavily on outbound prospecting, reps will end up spending quite a bit of time in the left half of the FT Quadrant as they search for opportunity. If you have a large number of inbounds, reps may end up with a lot of False Hope. If you do want to maintain geographic territories, you can still keep the active book small by using some of the timing automation described above.

Finally, hold reps accountable for working their book. Every rep has a maximum capacity; humans can only do so many things at once. One symptom of a rep “maxing out” is that they’re not actively working their book and especially if they’re not working their best prospects. Measure your reps on coverage of their book. You can use something as simple as “percent of accounts with an activity in the last X days” to get started. If reps don’t have the desired level of coverage, you have a few options. If you have a fixed book defined by geography or named accounts, you will likely have to deal with this through coaching and management attention. If you have a more flexible allocation model, you can consider also temporarily reducing their book size or pausing any inbounds that might be going to them while you coach them through their time management challenges.

I hope the FT Quadrant gives you a useful lens for thinking about your revenue processes. One of the things I like the most about revenue organizations is how it combines people and process to try to optimize an outcome. Humans have all kinds of interesting quirks that make them able to do extraordinary things but also make them vulnerable to various biases. It’s just how we’re wired; some things made a lot more sense on the savannah than they do in Salesforce. While we should always invest in training, coaching and mentoring our reps we also need to realize that how we orchestrate our systems has a huge impact on rep success and the success of our organization as a whole. Where possible, try to minimize the load on reps and move it into the system so that reps are free to focus on where they can have the most impact. With the right processes, your reps can stay in The Good Place without even trying.